With apologies for the long delay - we've been rushed off our feet in the stone yard....We were picked up at 9:00 am from our hotel by Sushil, my Granite supplier, and made our way out of Bangalore. On the way we drove through the ‘Silicon Plateau’ and saw huge office buildings with the names of huge multi-nationals on them (Intel, Hewlett Packard, etc.). Sushil told me that Bangalore was the educational capital of India with many students coming from other Indian states to attend the universities, institutes, and medical colleges. The energy and rate of growth reminded me of Singapore 20 years ago.

We soon left the city and drove out into the open countryside. It was greener and more lush than Rajasthan. We drove past vineyards and crops along the old road to Chennai, There wasn’t too much traffic, Sushil preferred this to the new road because the traffic was lighter and there was more to see.

On the way Sushil told me how he got his first big break in the Business. In 1992 the Dutch organisation CBI (Centre for the promotion of imports from developing countries) invited Sushil’s company to present his stone products and fill in a questionnaire about his business. They then reviewed his products along with others from India and also from other countries. Their criteria for selection were that he had product in demand in Europe and that he was following best practice production procedures. He made the shortlist, CBI then visited Sushil’s business and looked at the entire production cycle. His was the only Indian business that won their support. They paid for him to attend the Nuremburg stone show and gave him help to understand how to sell his product at the show. Sushil won his first export contract at the 1993 Nuremburg show and has attended the show every second year since, winning ever more export business. Now 14 years later he runs a substantial international company with exporting throughout Europe and North America.

As we drove along I was astounded to see that all the fenceposts in the area were made of granite. Later in the journey we saw some being put in post holes that were easily 2 metres long. It struck me as being a very good permanent solution, it was especially clear that it made sense when I noticed a termite mound next to one of these posts. A wooden fence post would soon be eaten!

We soon knew that we were in granite country when we drove past a hill of huge granite boulders, near the foot of which was the local Volvo dealership for heavy earth moving equipment. We were told that outcrops like this are protected and mining is not permitted although sometimes old traditional strip mines that produce stone use for the local market are allowed to continue operating. The granite area is vast, extending from 200km south of Bangalore to 800km north.

We could see that the infrastructure in the area was much more developed than in Rajasthan, the road we were travelling on was altogether better and electricity lines paralleled the road and lead to all the villages that we passed.

Before we left the main road we stopped at a roadside cafeteria for tea and bottled water.

About 90 km out of Bangalore we turned down a secondary road toward our first Quarry. We passed a village and asked if the people living in the local villages worked in the Quarries and were told that the often did but most were farmers. Along the side of the road were enormous hedges of Aloe Vera that both separate the fields and form a crop in it’s own right producing both jelly and a strong fibre.

We soon arrived at the first quarry. The license for this quarry had only recently been granted and it was in the very early stages of development. The area being worked was relatively small, perhaps 100 metres by 30 metres and no more than 5 metres deep at it deepest point.

The first few metres are a mixture of soil and larger and larger boulders below which in bedrock. It takes a year or more of development before the block coming out of the quarry is large enough for slab production. The material that is recovered in the earlier stages is used to produce landscaping products, aggregates, and other products for the domestic market. The larger boulders are drilled and broken using explosives. At the time of our visit there were only 5 people working at this quarry. Many of the workers in this area were Roman Catholics and some had already left to prepare for up coming Easter celebrations.

From this quarry we made our way to Sushil’s Factory. Along the way we saw examples of traditional quarrying. This is not for the export market but to produce fence posts and stone for local building work. The technique used is step mining, a very different technique from the deep quarries and modern mining techniques used to produce block for cutting into slabs.

We asked if there was illegal mining in the area. Sushil said that quarrying without a license is not allowed. He said that some people do it illegally. If they are caught they are arrested. Perhaps it might be the stone on a trailer behind a tractor, these people are like guerrillas. The might spend a few days somewhere quiet off the side of the road and then they are gone. Asked if any of this illegal stone goes to export, he said that no, it was very small scale, for the local market and was used as a free source of stone for building.

We asked about migrant workers. Sushil said that quarries are restricted areas because of the blasting. Unless they know someone they will not take them on, it’s the same for all the quarry owners. He cannot take the risk with the blasting materials, because they might get stolen and used for illegal work –and ‘…that would make us look bad’.

As we talked we passed a government tree plantation, the trees were being grown for use in restoring areas where quarrying operations were finished. Soon afterward we passed a wooded area that had once been a quarry. The only real hint of it’s past was that the largest trees were not that old and were all roughly the same size and also that although the terrain was rolling with small hillocks there were none of the granite outcrops and boulders that I would have expected to see.

Before long we arrived at Sushil’s factory. It was very impressive, at least on a par with any factory of its type I’d seen in Europe.

Everybody was wearing hard hats and boots. There were two of the biggest modern gang saws that I have ever seen and state of the art automatic slab polishing equipment. The factory had cranes for moving the slabs around. Slab that was being feed into the slab polishing machine using a tilting hydraulic tilting table which takes it from vertical to horizontal so that it can be fed into the machine.

Granite is very hard and so it takes 4 to 7 days of continuous cutting for the gang saw to cut through a block. The gang saw was simply too big to get into a single photograph, regrettably it wasn’t running at the time having just finished a cutting job it was being maintained for the next job. The photo shows the business end of one of the Italian gang saws. The 100 or more blades were being maintained at the time.

The block is taken off the delivery truck outside with a gantry crane (Photo 426) which then moves it to the single saw. The single saw is like a giant cheese wire except that the wire is a 8mm thick wire rope with lumps of diamond abrasive, like elongated beads along, fixed around it every few centimetres. This wire is pulled through the stone in a continuous loop to cut the sides of the block square ready for the big gang saws (photo 428). After this the block is concreted in place on a small flat deck truck with steel railway wheels and it makes its final journey into the gang saw on a rail tracks.

When the gangsaw is finished cutting the block into slabs each slab is marked to marked to show its provenance. The information captured is detailed, it shows which slab it is, how many were recovered from that block, which quarry it came from and where in the quarry the block came from.

There was some accommodation for unmarried workers on site as well as a small temple. Married workers live in nearby towns and villages.

This factory also produces tiles, which are cut from slab using smaller saws.

After we left the factory we saw more granite fence posts

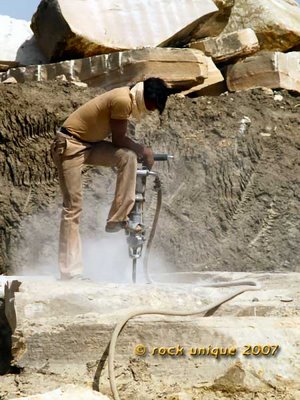

In a while we arrived at the second quarry of the day. This quarry was also in the early stages of development being less than a year into its lease. Again there were only a few people working, perhaps 5 or 6 on the site. They were in the later stages of removing the commercially less valuable material to get to the bedrock. Larger boulders were being drilled so that they could be reduced to sizes that heavy machinery could move and trucks can transport. The drilling was noisy work.

In contrast with the sandstone drilling in Rajasthan the holes being drilled in the granite quarries were deeper, up to a metre, and the stone was much harder. Again we were told that the workers refused to use safety equipment. One of the workers walked with a bad limp. I asked if it was a result of an injury at work and was told that no, he’s been like that since birth.

At the entrance to each quarry we noticed a stone painted blue that had the complete details of the mining lease for that quarry

We could see another quarry in the distance and went to visit.

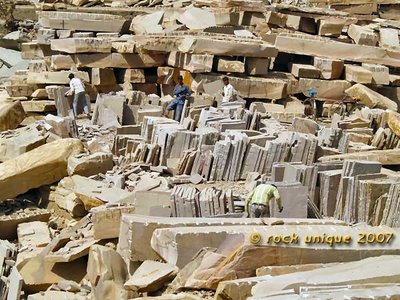

The third quarry of the day was about 4 years old and was well into the bedrock. When we arrived could see a large backhoe, as we had in each of the other quarries, and asked how they used such a large machine. We were told that the machine was leased compete with an experienced operator. This made economic sense to the quarry owner, particularly during the first few years when the costs of development exceed income.

In this quarry granite block was being recovered from the bedrock. The distinctive shear smooth faces left by a wiresaw were 8 to 10 metres high. The technique is to bore holes from the top and in from the side so that they meet deep inside the stone.

The wire is threaded through the hole, made into a loop, and attached to the drive unit for the wire saw.

In the photo above the wire can just be made out running from the top of the block to the drive unit. From the drive unit the wire runs back into the hole at the bottom .

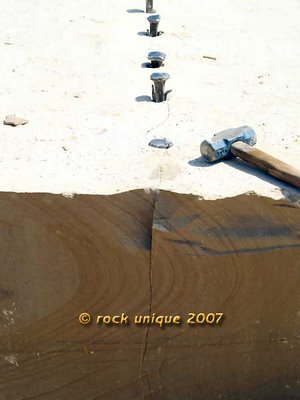

When the block is cut free of the bedrock the backhoe is used to pull the block over onto spoil to soften the landing. The block is then diced up for transportation by first drilling a row of holes in a line and then filling the holes with a compound that expands when it sets. By the next morning the block will be neatly broken into manageable pieces. Explosives are not normally used for this, as the shock wave from an explosion can cause damage throughout the bulk of the stone.

Another technique is to cut the block free and then, instead of toppling it, use the wiresaw to cut the block horizontally partway through at several levels. The backhoe then presses down on the top to snap it into a stack of manageably sized blocks. A bit like a loaf of sliced bread standing on end with 2 metre thick, 20 tonne slices!

The last quarry that we visited was quite large and very established. On the way in there were many safety signs

Near the pit was the blaster’s shelter

Block was being recovered on 4 levels.

It was getting toward the end of the day. We could see the compound being mixed to pour into holes to split blocks overnight.

This quarry was one of about 200 being run by the same company, one of the largest in the business. We stopped at the office,

We left and made our way back to Bangalore. We had a last visit to make to where Sushil produced his landscaping products. He processes granite into cobbles and other hard landscaping on a site of a few acres in Bangalore itself. It was quite dark at the yard, and work had finished for the day. we could see the piles of raw material, finished cobbles, and waste. The manager was there to meet us and we saw what we could in the headlights of the car. I was struck by the fact that we were in the city less than a mile from a busy highway and in a commercial area with huge factories and corporate headquarters. I could not for one moment believe that there would be child labour or worker exploitation in such a visible location in a major city.